🌾 Welcome to StableBread’s Newsletter!

In a previous post, we covered how to estimate earnings growth from company fundamentals.

Now, we’ll explain how to estimate growth in operating income, which shows how well a company’s core business operations are expanding before considering financing and tax decisions.

This post draws from Aswath Damodaran’s 2025 book “Investment Valuation” (4th edition), to show you how operating income growth connects directly to (1) how much a company reinvests in its business and (2) the return the company earns on its invested capital.

We'll consider two main scenarios for estimating operating income growth:

Companies with stable returns on capital.

Companies with changing returns on capital (either improving or declining).

These scenarios will help you create more accurate growth forecasts for different types of businesses regardless of their current performance.

📜 Aswath Damodaran is a Finance Professor at NYU Stern School of Business who is widely known for his expertise in valuation and corporate finance. He has written several textbooks on valuation methods and provides free investment tools and data on his website.

💻 Excel Model: Download this free Excel model to follow along: Estimating Operating Income Growth (THO) - StableBread

Stable Return on Invested Capital

For companies with a stable return on invested capital (defined below), we can calculate expected operating income (aka EBIT) growth using this formula:

Expected GrowthEBIT = Reinvestment Rate × Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

where:

Reinvestment Rate = (CapEx - Depreciation + △ Non-Cash WC) / (EBIT × (1 - Tax Rate))

ROIC = (EBIT × (1 - Tax Rate)) / (Shareholders’ Equity + Total Debt - Cash and Equivalents)

This formula shows that operating income growth comes from two components: (1) the portion of profits a company reinvests and (2) the returns it generates on that investment (as discussed above).

Both measures should be forward-looking estimates that reflect what the company will likely achieve in the future, not just what happened in the past.

Reinvestment Rate

The reinvestment rate measures what percentage of after-tax operating profits a company puts back into its business. This includes:

Net capital expenditures (CapEx minus depreciation).

Changes in working capital (accounts receivable, inventory, and accounts payable).

When estimating future reinvestment rates, using only the most recent year may not be optimal because:

Some companies invest in relatively few large projects, creating uneven annual spending (e.g., manufacturing company building a new factor every five years).

As companies grow and mature, their reinvestment needs (and rates) typically decrease.

For these reasons, calculating an average reinvestment rate over several years often provides a more reliable estimate.

Industry averages can also help, especially for companies that have grown significantly and may be transitioning to more typical reinvestment patterns.

Note: For companies in research-intensive industries, R&D expenses should be treated as CapEx rather than operating expenses when calculating the reinvestment rate. This adjustment ensures we capture all investments in future growth.

Negative Reinvestment Rates

A negative reinvestment rate occurs when:

Depreciation exceeds CapEx

Working capital declines substantially

For most companies, this is temporary, reflecting uneven CapEx or fluctuating working capital. In these cases, using multi-year averages or industry benchmarks is more appropriate.

Sometimes negative reinvestment reflects incomplete accounting. Companies growing through acquisitions might not include those acquisitions in CapEx figures. Companies that don't capitalize R&D expenses may appear to have lower reinvestment than reality.

Other times, negative reinvestment is deliberate:

Companies that overinvested in the past can maintain operations for years without significant new investment, temporarily boosting cash flows.

Some companies intentionally shrink by not replacing worn assets and reducing working capital, essentially liquidating gradually.

How we handle negative reinvestment depends on the cause:

For temporary situations, use multi-year averages or industry benchmarks.

For companies deliberately shrinking, use the actual negative rate. This correctly shows negative expected growth and declining earnings over time.

Return on Invested Capital

Return on invested capital (ROIC) measures how efficiently a company generates profits from the money it has invested in its business. Calculating it accurately involves several challenges:

Book value limitations: The balance sheet shows historical costs and accounting depreciation rather than the true capital invested in existing assets. Additionally, operating leases (rental agreements for stores, warehouses, or equipment) are often excluded from book value but represent real invested capital that should be included.

Operating income distortions: Accounting rules for measuring operating income may not capture the full economic reality of the business, particularly when companies use different depreciation methods or have unusual one-time expenses.

Future returns vs. existing returns: The return on current investments often differs from what the company will earn on future investments. High returns attract competition, which typically drives returns down over time.

This last point is particularly important for growth estimates. When a company earns returns well above its industry average, new competitors enter the market and existing rivals copy successful strategies.

Companies with exceptionally high returns on capital should therefore use conservative estimates for future returns, adjusting their forecasts downward to reflect the reality that competition will likely reduce their profitability over time.

Note: Companies that consistently earn returns above their cost of capital (ROIC > COC) are generating excess returns from competitive advantages or barriers to entry. When these high returns persist for many years, it indicates the company has a durable competitive advantage.

Positive and Changing Return on Invested Capital

Many companies experience changes in their ROIC over time. When this happens, the growth formula needs an additional component:

Expected GrowthEBIT = [ROICt × Reinvestment Rate] + [(ROICt - ROICt-1) / ROICt-1]

This formula captures two types of growth:

First term: Represents growth from new investments, just like in the stable return scenario.

Second term: Represents the additional growth (or decline) that comes from improving the returns on assets the company already owns.

When a company becomes more efficient with its existing assets, it generates more income from the same invested capital. This improvement creates a one-time boost to earnings growth.

The key word here is “one-time” because this extra growth only happens in the year when returns improve. After that, growth returns to the normal rate determined by reinvestment and the new ROIC.

Let’s use an example of a company that improves its ROIC from 10% to 11% while maintaining a 20% reinvestment rate:

Expected GrowthEBIT = [0.11 × 0.20] + [(0.11 - 0.10) / 0.10] —> 12.2%

This 12.2% growth rate only applies for one year. The following year, if the company maintains its 11% ROIC and 20% reinvestment rate, growth will return back to 2.2%.

The same logic works in reverse. Companies facing increased competition or operational challenges might see their returns decline, which creates a drag on growth beyond just the effect on new investment.

For instance, if returns fell from 11% to 10% with the same 20% reinvestment rate, the growth would drop to -7.8% for that year:

Expected GrowthEBIT = [0.10 × 0.20] + [(0.10 - 0.11) / 0.11] —> -7.8%

Marginal and Average ROIC

When analyzing ROIC, we need to distinguish between two measures:

Marginal ROIC: The return earned by the firm on just its new investments in a given year.

Average ROIC: The return earned by the firm on all its investments collectively.

This distinction matters because it affects how we calculate expected growth in operating income.

Changes in marginal returns don't create the additional growth boost or drag we discussed earlier. When only marginal returns change, expected growth equals the reinvestment rate times the marginal return.

Changes in average returns, however, will produce the additional impact on growth shown in our expanded formula. This happens when new investments earn significantly different returns than existing ones, gradually shifting the company's overall profitability.

For example, if a company's new investments earn 15% while existing assets only earn 10%, the average return will gradually rise. This creates additional growth beyond what new investments alone would generate.

Candidates for Changing Average ROIC

Two types of companies are likely to see significant changes in their average ROIC:

Companies improving from poor performance: These businesses have low returns with significant room for improvement. They might be recovering from past mismanagement or implementing new strategies. When they improve efficiency, the growth impact can be significant. A company improving its ROIC from 5% to 10% gets both doubled growth from new investments and a 100% earnings boost from existing assets. This explains why turnaround situations produce exceptional growth rates.

Companies with unsustainably high returns: Companies earning 30% or 40% ROIC attract competitors who want those profits. New entrants copy successful strategies while existing competitors invest heavily to gain market share. As competition intensifies, returns decline on both new and existing investments.

Understanding which category a company falls into helps predict whether its average ROIC will rise, fall, or remain stable. Ultimately, changes in average returns can have a larger impact on near-term growth than the reinvestment rate itself.

Estimating Thor Industries’ Operating Income Growth

We’ll use Thor Industries ($THO ( ▼ 1.17% )), an American manufacturer of towable and motorized RVs, as our example company for estimating growth in operating income across three different scenarios.

Scenario #1: Stable ROIC

To evaluate Thor's growth potential, we first need to examine how much the company reinvests in its business.

The following table shows Thor's reinvestment patterns over the past five years, with aggregate totals (USD in millions):

Reinvestment Rate ($THO)

Thor's reinvestment patterns show significant volatility over the past five years.

The negative reinvestment rates in FY2020, FY2023, and FY2024 indicate the company was releasing capital rather than investing, likely through working capital reductions and spending less on CapEx than the depreciation of existing assets.

The aggregate reinvestment rate of 1.1% represents minimal net investment over the entire period.

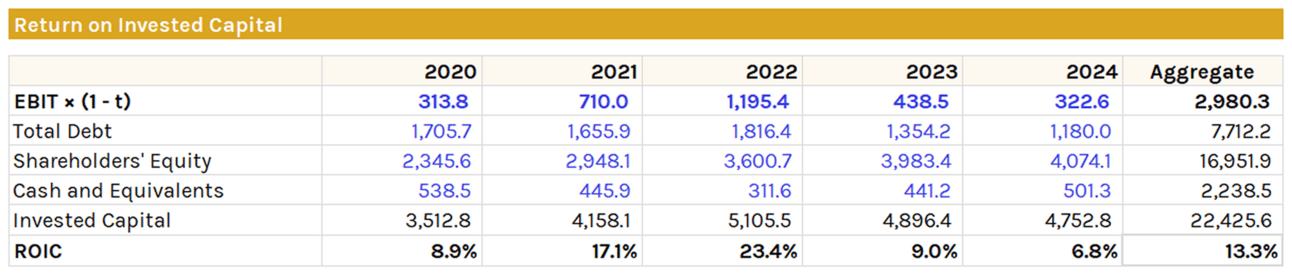

Next, we need to see what returns Thor generates when it does invest capital. The table below shows ROIC calculations for the same five year period (USD in millions):

ROIC ($THO)

The ROIC also displays considerable variation, ranging from 6.8% to 23.4%. The aggregate ROIC of 13.3% provides a more stable baseline for projections.

Now, we can apply the stable return formula:

Expected GrowthEBIT [$THO] = Reinvestment Rate × ROIC

—> 1.1% × 13.3% —> 0.14%

This near-zero growth rate of 0.14% reflects Thor's minimal reinvestment activity. With only 1.1% of operating income being reinvested back into the business, even a respectable 13.3% return generates negligible growth.

Note: These calculations use reported figures without adjustments for R&D capitalization or operating lease treatment, both for simplicity and because Thor has limited R&D spending and lease obligations. Damodaran recommends capitalizing R&D as it creates future value, and treating operating leases as debt since they represent financing obligations.

Scenario #2: Declining ROIC

Now assume Thor's ROIC drops to 10% in FY2025, down from the historical aggregate of 13.3%.

This could occur due to increased competition, market saturation, or declining operational efficiency in the RV market. The reinvestment rate remains at 1.1%.

The expanded formula accounts for the one-year change in returns:

Expected GrowthEBIT [$THO] = [ROIC₂₀₂₅ × Reinvestment Rate] + [(ROIC₂₀₂₅ - ROIC₂₀₂₄) / ROIC₂₀₂₄]

—> [10% × 1.1%] + [(10% - 13.3%) / 13.3%] —> -24.6%

This calculation shows Thor would face a 24.6% decline in operating income for FY2025.

The drop from 13.3% to 10% returns causes a substantial negative impact that far outweighs any positive contribution from new investments at the lower return rate.

Scenario #3: Improving ROIC

While the Auto & Truck industry average ROIC currently sits at just 3.15% (Damodaran), we’ll assume Thor maintains its position as an industry leader rather than converge toward this low average.

Let's consider an optimistic scenario where management's strategic initiatives improve returns from the current 13.3% to 15% over the next five years.

We calculate the expected annual growth rate for this gradual improvement scenario as follows:

Expected GrowthEBIT [$THO] = ROICmarginal × Reinvestment Rate + {[1 + (ROICin 5 years - ROICcurrent)/ROICcurrent](1/5) - 1}

—> 15% × 1.1% + {[1 + (15% - 13.3%) / 13.3%](1/5) - 1} —> 2.62%

Similar to scenario #1, this 2.62% growth rate is positive but modest. Thor's minimal 1.1% reinvestment rate constrains growth potential, even when returns improve.

The company appears to prioritize returning cash to shareholders over pursuing aggressive growth, a strategy that may reflect Thor's mature position in its competitive lifecycle.

Thanks for Reading!