🌾 Welcome to StableBread’s Newsletter!

Range-bound markets occur when stock indexes move sideways for years after bull markets push valuations too high. During these periods, earnings growth and P/E compression offset each other, resulting in flat overall returns.

Vitaliy Katsenelson's 2007 book "Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets" shows that growth helps offset the P/E compression that reduces returns during these periods. As valuations contract, only companies with genuine earnings expansion can deliver positive results for shareholders.

However, not all growth is created equal. Some sources are temporary, while others can sustain a company through decades of market stagnation. The key lies in finding companies with multiple reliable growth engines selling at reasonable prices.

Sources of Growth

Katsenelson identifies two fundamental sources of returns for investors:

Earnings growth: The expansion of company profitability over time (expressed as earnings or cash flows growth).

Dividends: Direct cash payments to shareholders (expressed as dividend yield).

These two sources work together to reduce "dead money" risk, where out-of-favor stocks stay undervalued for extended periods.

Dividends provide real-time compensation while you wait, and growing earnings compress valuations by increasing the denominator in the P/E ratio, allowing investors to generate returns even during sideways markets.

For example, if you buy a stock at 15x earnings with $1 in current earnings, and the company grows earnings 15% annually, those earnings will double to $2 in ~5 years (rule of 72: 72/15 = 4.8 years).

Even if the P/E never recovers and settles at 12x, the stock price would rise to $24 (12x × $2 earnings), delivering a 10% annual return despite multiple compression.

Time becomes your ally when earnings are rising and dividends are steadily deposited in your brokerage account, but without them, time erodes your opportunity cost as capital sits idle.

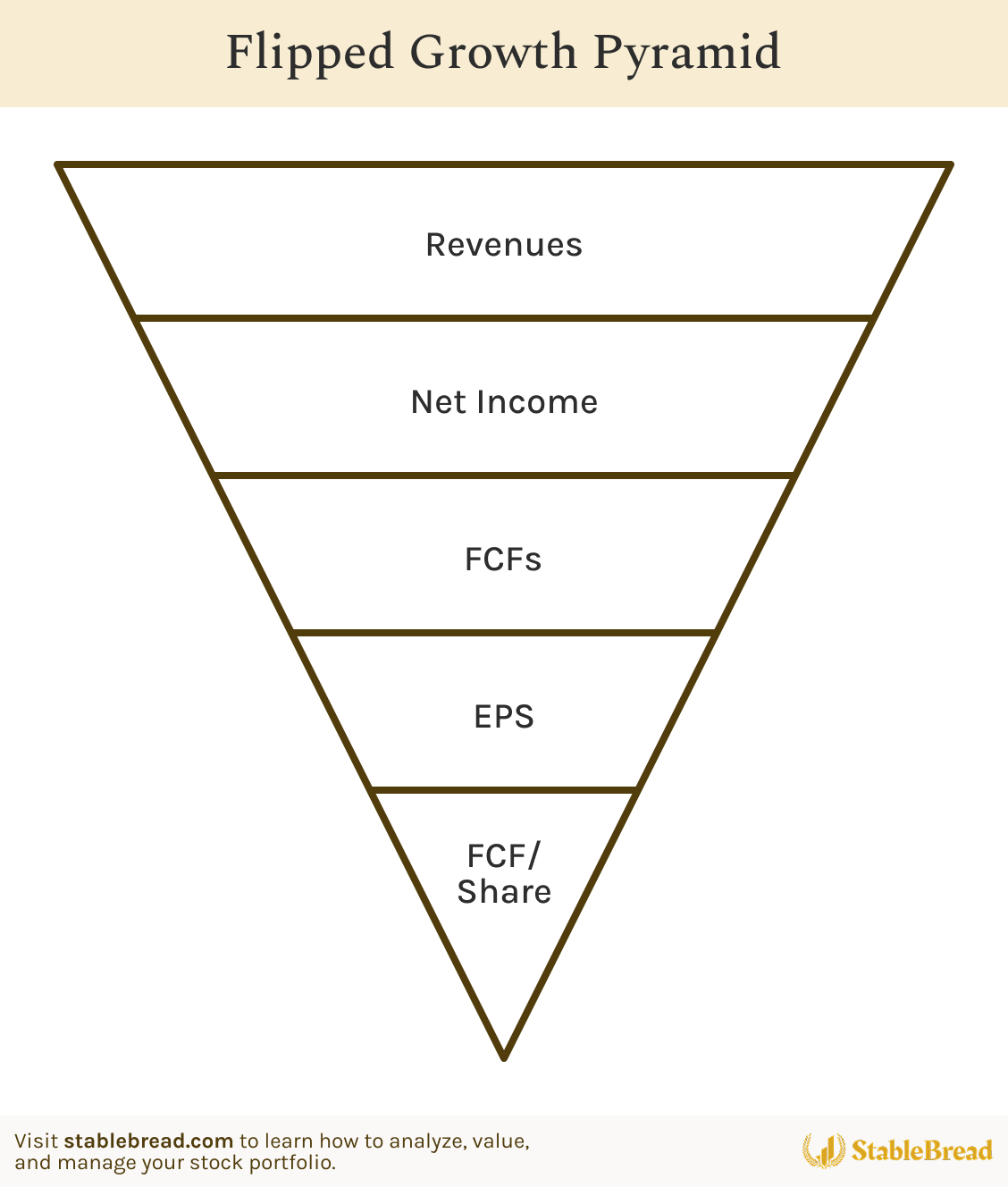

Flipped Growth Pyramid

Katsenelson visualizes growth sources as an inverted pyramid, with revenue at the wide top flowing down to the narrower bottom of earnings and cash flow per share:

Flipped Growth Pyramid

It's important to understand the sources of a company's profitability growth. As you move down the pyramid, value creation can occur at each level:

If costs grow slower than revenues, margins expand and net income growth outpaces revenue growth.

When companies buy back shares, the share count declines, accelerating per-share growth.

Efficient management of assets and working capital can make free cash flow growth exceed earnings growth.

You should evaluate each level to determine whether it creates or destroys value. For instance, a company might show strong revenue growth while destroying value through poor margin management or wasteful capital allocation.

Moreover, all growth sources eventually face limits. What drove past growth may be near exhaustion, so investors should regularly assess each driver's remaining potential and track whether actual results match expectations.

Revenue Growth Strategies

Companies with multiple revenue drivers fare better in range-bound markets than those dependent on a single growth strategy.

Katsenelson outlines several paths to organic revenue growth (i.e., growth from existing operations):

Volume expansion: Selling more products/services to existing and/or new customers represents the most straightforward growth path. This includes geographic expansion into new markets (domestic or international). Many companies find renewed growth opportunities by entering international markets after saturating their home territories.

Pricing power: Raising prices works when demand elasticity allows it (how much price increases affect customers' willingness to buy), though pricing power depends on competitive advantages and barriers to entry. Higher prices eventually attract new competitors or push customers away, making this a finite strategy.

Strategic price reductions: Counterintuitively, lowering prices can drive growth if volume increases offset price declines and enable cost reductions. For example, lower prices in the wireless industry stimulated cell phone usage and allowed companies to spread fixed network costs across larger subscriber bases.

Growth by acquisition offers another path, though it's typically more expensive than organic growth. Moreover, acquisitions bring external risks like integration challenges and operational conflicts that organic growth avoids.

Margin Expansion

Margin improvements represent another growth driver, coming primarily from two sources:

Operating Efficiency

Technological innovations have enabled significant efficiency gains across industries.

However, Katsenelson warns that efficiency improvements rarely provide lasting advantages. As technology becomes available to all competitors, cost structures converge and customers capture the benefits through lower prices.

Cost cutting also faces natural limits. While a company might successfully reduce costs for years, it eventually hits a ceiling. Once reached, growth stops completely.

Katsenelson also cautions that companies must ensure cost cutting doesn't sacrifice future growth. Some companies slash R&D to boost short-term profits, leaving them vulnerable when competitors bring innovations to market.

Economies of Scale

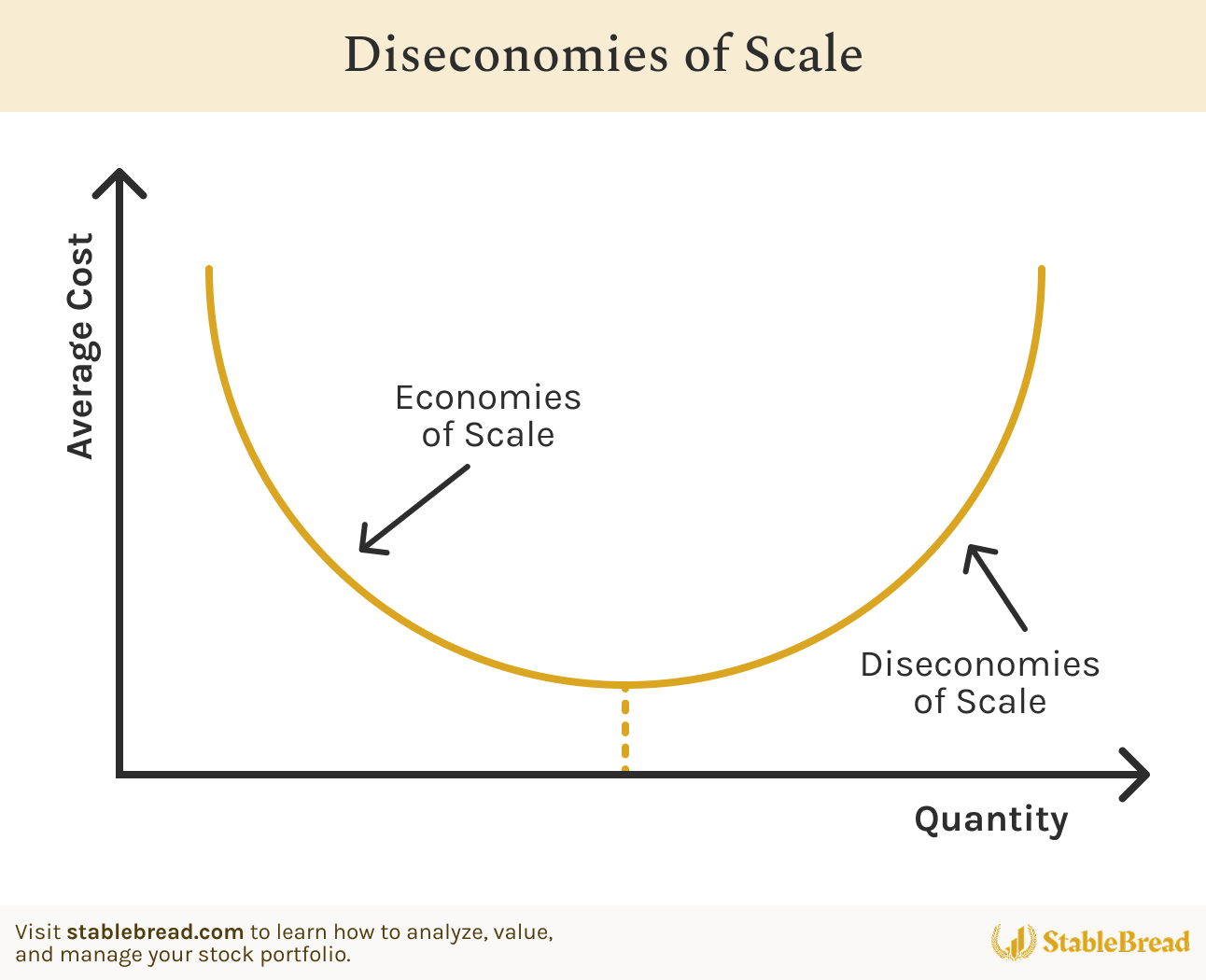

Economies of scale occur when a company’s average costs decrease as production volume increases. As production grows, fixed costs are divided among more units, reducing the average cost per unit.

In contrast, diseconomies of scale occur when competitors losing market share must cover the same fixed costs with fewer sales, reducing their profitability.

Diseconomies of Scale

While economies of scale are more sustainable than pure efficiency gains, they require two ingredients: (1) sales growth and (2) high fixed costs. As sales increase over a fixed cost base, margins naturally expand.

However, similar to efficiency gains, companies rarely capture all these margin gains. When competitors enjoy similar scale benefits, competition forces companies to pass savings to customers through lower prices.

Software is the obvious example of unlimited economies of scale. Whether Microsoft sells one copy of Windows or one million copies, the development cost remains the same. Each additional sale is nearly pure profit since reproducing software costs almost nothing.

Lastly, industry structure significantly influences scale benefits. As Katsenelson notes:

"If a company’s competitors outsource manufacturing while the company keeps manufacturing in house, that company’s economies of scale increase with the rise of volume, whereas competitors may not benefit to the same degree, since a lower portion of their costs is fixed."

Thus, companies with high fixed costs gain more from scale than those who outsource production and maintain variable cost structures.

Growth Sustainability

Stock Buybacks and Capital Allocation

Share repurchases can improve earnings per share (EPS) growth by reducing the share count, but their effectiveness depends entirely on execution. When combined with dividends, buybacks reduce the growth burden on companies.

For example, a company targeting 12% total return with a 3% dividend yield and 2% share buyback (of shares outstanding) only needs 7% earnings growth, rather than 12% without these capital returns. This lower growth requirement typically means less business risk.

Management often makes poor capital allocation decisions with buybacks because of three key factors:

Emotional bias: They typically overestimate their company's value due to attachment built from years of investment in the business.

EPS manipulation: They may prioritize meeting Wall Street targets over shareholder value, destroying wealth to make the numbers.

Poor timing: They often buy most aggressively when shares are expensive, sometimes at valuations exceeding 30 times earnings.

Katsenelson notes that if you conclude a company shouldn't buy back stock at current valuations, you should question whether you should own it yourself.

Buybacks from FCF are sustainable and less risky than those requiring increased leverage. While any buyback reduces equity and increases the debt-to-assets (D/A) ratio, the funding source creates an important distinction:

High leverage scenario: Borrowing to buy shares increases debt levels and interest expenses, potentially pressuring valuations and offsetting buyback benefits. Debt capacity also creates firm limits.

Low leverage scenario: Using FCF maintains stable debt levels and interest coverage ratios. As long as cash generation continues, companies can keep repurchasing shares.

Ultimately, Katsenelson suggests evaluating buybacks by asking four questions:

Is the stock undervalued?

What motivates management's buyback decision?

Is the company leveraging its balance sheet?

Does a better use for cash exist?

These questions help distinguish value-creating buybacks from those that waste shareholder capital.

Note: Companies that buy back meaningful amounts of stock while paying dividends and growing earnings require significant free cash flows (FCFs) and high returns on capital. They also need to trade at attractive valuations, since both dividend yield and buyback effectiveness depend on stock price.

Working Capital and One-Time Gains

Improvements in working capital management can generate substantial cash flows without requiring sales growth.

Companies can free cash through several methods:

Extending payment terms to suppliers (increasing accounts payable days).

Reducing inventory through better supply chain management.

Collecting receivables faster.

These changes shift financing burdens to suppliers or customers, freeing cash for dividends, buybacks, or growth investments.

However, working capital improvements typically provide one-time benefits rather than ongoing growth, as once you’ve optimized payment terms and inventory levels, those gains can’t be repeated.

Distinguishing Past From Future Growth

Katsenelson strongly warns against projecting past growth rates into the future without understanding their sources:

"Just because a company was able to rely on a source of growth in the past doesn't mean it can count on it in the future. I strongly recommend you not project past growth into the future with blind linearity. To forecast the future, you need to really understand the past."

Growth engines that powered past performance may be exhausted or approaching limits. Decomposing historical growth helps you understand what actually drove results:

How much came from revenue growth versus margin expansion?

What portion resulted from share buybacks versus organic growth?

Which growth drivers remain viable going forward?

For instance, a company showing 13% historical earnings growth might have generated only 2% from sales, with the rest from cost cutting and buybacks. If margins have peaked and the company bought shares at high valuations, future growth will likely disappoint investors extrapolating past trends.

Identifying Future Growth Engines

Rather than relying on single growth drivers, Katsenelson advocates identifying multiple engines that can work together. This approach reduces risk, as temporary stalls in one area won't derail overall growth.

Katsenelson gives the example of Jackson Hewitt, a tax preparation company, where he identified five growth engines:

Store maturation: Newer locations process more returns as they mature (estimate 3-6% volume growth).

Price increases: Inflation plus growing tax complexity drives pricing (estimate 4-6% annually).

New locations: Market share gains in fragmented industries (estimate 3-6% revenue growth).

Operating leverage: Fixed costs spread over growing revenue base (estimate 2-3% margin expansion).

Capital allocation: Buybacks and dividends from excess cash flow (estimate 5-7% EPS growth).

For each engine, estimate a range rather than a single number. In Katsenelson's case, this created scenarios showing 17-28% potential EPS growth, depending on how each engine performs.

Overall, companies with multiple viable growth engines offer more predictable expansion and lower risk than those dependent on single factors.

Dividends in Range-Bound Markets

Dividends vs. Buybacks

Katsenelson argues that while theoretically equivalent to buybacks, dividends provide superior value in practice. The premise is that management will eliminate almost any expense before cutting dividends, as cuts signal distress and can devastate stock prices.

Katsenelson emphasizes that dividends transfer wealth from corporate accounts (which shareholders don't control) to brokerage accounts (which they do). This liquidity transformation matters, particularly when companies face trouble. Once paid, dividends cannot be reclaimed, while retained earnings can disappear during difficulties.

Additionally, significant dividends create a floor under stock prices. When share prices fall, dividend yields rise, attracting income-seeking investors and potentially reducing downside volatility.

Value of Dividends in Range-Bound Markets

Katsenelson observed that dividends represent 90% of total returns during range-bound markets, compared to just 19% during bull markets. This difference stems from the lack of capital appreciation when markets move sideways.

Jeremy Siegel (an American economist), quoted by Katsenelson, explains how dividends protect and amplify returns during market cycles:

"The greater number of shares accumulated through reinvestment of dividends cushions the decline in the value of the investor's portfolio. But extra shares do even more than cushion the decline when the market recovers. Those extra shares will greatly enhance future returns. So in addition to being a market protector, dividends turn into a 'return accelerator' once stock prices turn up."

Thus, during range-bound markets, dividends provide three key benefits:

Real-time compensation: Investors get paid while waiting for valuations to recover.

Return acceleration: Reinvested dividends buy more shares at depressed prices, amplifying eventual recoveries.

Confidence signal: Substantial dividends indicate genuine cash generation, reducing accounting manipulation risks.

Given these benefits, Katsenelson argues that broad market indexes won't provide adequate dividend protection. Instead, investors need portfolios of above-average yielding stocks to capture these range-bound market benefits.

Debunking the High Dividend, Low Growth Myth

Academic theory suggests high dividend payouts should slow earnings growth by reducing reinvestment capital. However, empirical evidence contradicts this assumption for mature companies generating substantial free cash flow.

Research by Cliff Asness and Robert Arnott found that companies with higher payout ratios actually grew earnings faster than those retaining more profits. Their study concluded:

"The historical evidence strongly suggests that expected future earnings growth is fastest when current payout ratios are high and slowest when payout ratios are low. This relationship is not subsumed by other factors, such as simple mean reversion in earnings."

This counterintuitive result reflects the discipline dividends impose on management. High payouts force executives to maximize the value of retained dollars rather than pursuing "empire building" or wasteful investments. Cash not distributed may be wasted on low-return projects or expensive acquisitions that destroy shareholder value.

Dividends in Context

Katsenelson references David Dreman's research from "Contrarian Investment Strategies: The Next Generation" to provide important context about dividend performance across market cycles.

Dreman's study from 1970 to 1996 covered 12 years of the 1966-1982 range-bound market and 14 years of the 1982-2000 bull market.

During market declines when the average stock dropped 7.5%, high-dividend portfolios fell only 3.8%, while low P/E portfolios declined 5.7%.

However, Dreman found that despite outperforming the market, high dividend strategies proved inferior to strategies based on low price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, price-to-cash flow (P/CF), and price-to-book (P/B) metrics.

The takeaway from Dreman's research is that dividends matter, but not in isolation. The best approach, according to Katsenelson, is to evaluate high dividends in the context of P/E contraction and earnings growth.

Thanks for Reading!