🌾 Welcome to StableBread’s Newsletter!

In a previous post, we introduced the concept of 100-baggers—stocks that return $100 for every $1 invested. We also discussed the coffee-can portfolio strategy for holding these exceptional investments through market cycles.

These concepts draw from Thomas Phelps' 1972 book "100 to 1 in the Stock Market" and Christopher Mayer's 2015 "100 Baggers: Stocks That Return 100 to 1 and How to Find Them."

Mayer's research found 365 stocks that returned 100x from 1962 to 2014. He discovered clear patterns and turned them into screening criteria to find future 100-baggers. This post explains the criteria so you can identify these stocks for your portfolio.

📜 Thomas Phelps

Thomas Phelps had a varied 42-year career in markets as the WSJ's Washington bureau chief, a Barron's editor, partner at a brokerage firm, and finally partner at Scudder, Stevens & Clark.

📜 Christopher Mayer

Christopher Mayer began as a corporate banker before becoming the editor of Capital & Crisis newsletter in 2004. He now manages Woodlock House Family Capital.

100-Bagger Screening Framework

Market Size

Market capitalization is the total value of a company's outstanding shares (share price × shares outstanding).

The median sales figure in Mayer's study was ~$170 million with a median market cap of ~$500 million, placing them in the small-cap category.

These companies are large enough to have proven business models but small enough to have significant expansion potential ahead.

After all, a $50 billion company would need to become a $5 trillion company to achieve 100-bagger status, which is virtually impossible in a reasonable timeframe. For reference, currently only 12 companies worldwide have exceeded $1 trillion in market cap.

Put simply, small companies can grow by 10 to 20 times and still have room for even more growth. This makes it easier for small companies to become 100-baggers relative to larger ones.

Return on Equity

Return on equity (ROE) measures how efficiently a company generates profit from its equity:

ROE = Net Income / Shareholders’ Equity

Companies that consistently achieve high returns on equity (i.e., 20% or more for several consecutive years) often become exceptional long-term investments.

Mayer highlights Home Capital Group, a Canadian consumer finance company that maintained ROEs between 20-30% for 15+ years. Its stock price returned 49x over 16 years, with an annualized stock return of 28%—closely matching its average ROE over that period.

This correlation between ROE and long-term stock returns exists because consistent high ROE allows a company to compound its capital base over time.

"Over time, the return of a stock and its ROE tend to coincide quite nicely."

When evaluating ROE, you should understand how companies achieve these returns. Consider two companies both reporting 25% ROE:

Company A: Generates ROE through a healthy 10% profit margin with minimal debt.

Company B: Achieves the same ROE with just 5% profit margin but twice the leverage.

During economic headwinds, Company A would likely maintain its performance due to operational efficiency, while Company B's ROE could collapse under the weight of its debt obligations.

Note: Sometimes we need to look beyond reported earnings. Amazon ($AMZN ( ▲ 0.18% )) spent billions on R&D ($22.6B in 2017 alone—highest in the U.S.), which reduced reported profits. By prioritizing reinvestment over short-term earnings, Amazon grew into one of the world's largest companies, delivering extraordinary shareholder returns.

Owner-Operators

Some of history's greatest 100-baggers had significant insider ownership: Sam Walton at Walmart ($WMT ( ▲ 0.24% )), Jeff Bezos at Amazon ($AMZN ( ▲ 0.18% )), and Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway ($BRK.A ( ▲ 0.14% )), to name a few.

"If management and the board have no meaningful stake in the company—at least 10 to 20% of the stock—throw away the proxy and look elsewhere."

Notably, a 2012 study conducted by Joel Shulman and Erik Noyes found companies managed by billionaires outperformed market indexes by 7% annually.

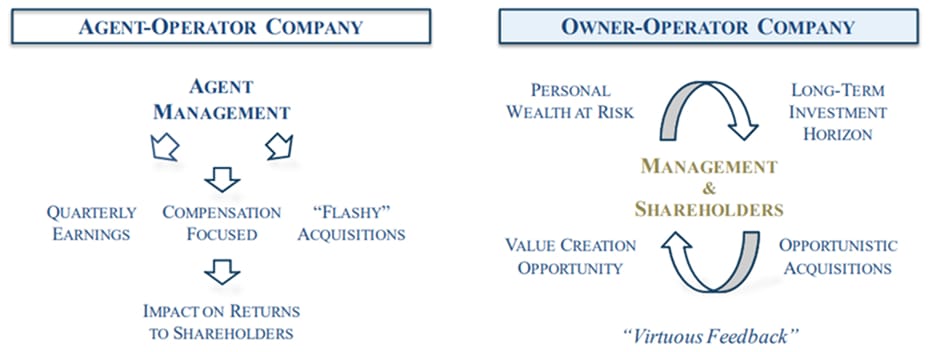

The premise behind this outperformance is that when CEOs and key executives have significant personal wealth tied to the company's performance, they make decisions with a long-term perspective. The evidence suggests they're less inclined to chase quarterly earnings at the expense of sustainable growth and may allocate capital more wisely.

Mayer uses this graphic in his book to illustrate the difference between the typical public company and owner-operators:

Source: Kinetics Funds

High insider ownership also typically correlates with better corporate governance. Competent owner-operators with good capital allocation skills often take on more debt and deploy additional cash during recessions when good opportunities arise, rather than hoarding it. They tend to view market downturns as opportunities to expand while others retreat.

Superior Capital Allocation

The greatest 100-baggers were often led by CEOs who excelled at capital allocation—deciding where to invest the company's resources for maximum long-term returns.

In his book "The Outsiders," William Thorndike profiled exceptional CEOs who delivered extraordinary shareholder returns through superior capital allocation.

These "Outsider" CEOs (called this because they operated outside conventional management wisdom) share several characteristics:

Focus on per-share value: They prioritize metrics that directly benefit shareholders (i.e., EPS, BVPS, and FCFPS) rather than simply growing total revenue or market share.

Disciplined acquisitions: They make acquisitions that genuinely add value rather than empire-building.

Strategic share repurchases: They buy back shares aggressively when prices are attractive.

Operational efficiency: They maintain lean operations with minimal bureaucracy.

Independent thinking: They make decisions based on business fundamentals rather than following industry trends.

To help identify these value-focused leaders, read several years of shareholder letters and conference call transcripts. Look for management teams that discuss return on invested capital (ROIC), per-share value growth, and thoughtful capital allocation strategies rather than just quarterly results.

Economic Moat

An economic moat refers to a company's ability to maintain competitive advantages over its rivals, protecting its market share and profitability over time. For a company to compound at extraordinary rates for decades, this protection is essential.

Look for businesses with strong moats that might come from:

Strong brands: Command premium prices despite similar underlying products (e.g., Apple ($AAPL ( ▼ 0.68% )) charging premium prices for smartphones).

High switching costs: Create "sticky" customer relationships (e.g., Adobe's ($ADBE ( ▲ 5.33% )) creative software that professionals rely on).

Network effects: Products/services that become more valuable as more people use them (e.g., Visa's ($V ( ▲ 1.27% )) payment network growing stronger with each new merchant).

Cost advantages: Allow for lower prices while maintaining profitability (e.g., Costco's ($COST ( ▼ 0.13% )) membership model and efficient operations).

Size advantages: Either absolute scale or dominance within specific niches (e.g., Amazon's ($AMZN ( ▲ 0.18% )) e-commerce dominance and logistics network).

Companies with these moat characteristics can sustain high returns far longer than those competing solely on price or in commoditized industries.

Related: How to Identify an Economic Moat

Mayer found that the best indicator of a durable competitive advantage was consistently high gross margins—particularly those significantly exceeding industry averages.

Gross profit margin (COGS / revenue) indicates the price customers are willing to pay for a product/service over its cost and serves as a measure of value added to the customer.

Matthew Berry's research, cited by Mayer, found that gross margins are "surprisingly resilient" to mean reversion. While many financial metrics tend to trend toward average over time, Berry discovered that gross margins were persistent—companies with high margins tend to maintain them, while those with low margins typically remain low.

This resistance to mean reversion suggests that companies with high gross margins have a sustainable competitive advantage, making them more likely to become 100-baggers.

Earnings Growth and Multiple Expansion

100-baggers typically benefit from the combination of two key factors: earnings growth and valuation multiple expansion. Mayer calls these the "twin engines" of extraordinary returns.

More specifically, these engines refer to increasing earnings per share (EPS) and expanding price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios that together multiply investor returns.

Earnings per share (EPS) represents a company's profit divided by its outstanding shares:

EPS = Net Income / Number of Outstanding Shares

A higher EPS indicates the company is generating more profit for each share owned. Growing EPS over time typically reflects an expanding and increasingly profitable business.

The price-to-earnings (P/E) shows how much investors are willing to pay for each dollar of earnings:

P/E Ratio = Share Price / EPS

A P/E of 20x means investors are willing to pay $20 for every $1 of current earnings. Higher P/E ratios often indicate the market expects stronger future growth.

For long-term investors, a simplified approximation of returns can be expressed as:

Total Return ≈ Earnings Growth × Change in P/E Growth

This formula illustrates the power of the twin engines. For example, if earnings grow 20-fold and the P/E ratio expands from 10x to 50x, the stock could deliver a 100-fold return (20 × 5 = 100x).

"Over a long period of time, it's hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns."

While strong business performance drives long-term returns, exceptional results often come when the market also places a higher value on those earnings over time.

But what should you do when a stock's P/E grows extremely high?

Mayer examined different opinions on handling “lofty P/E ratios” and concludes that investors should be "reluctant sellers."

The decision boils down to whether (1) your investment thesis about the company's fundamentals remains valid and (2) if you can still sleep soundly at night when a stock becomes highly overvalued.

When screening for potential 100-baggers, look for companies with consistently strong earnings growth over multiple years with valuations that provide room for multiple expansion. The ideal candidates operate in large addressable markets that allow for sustained growth while currently capturing only small portions of those markets.

Strategic share buybacks can substantially accelerate returns for long-term shareholders. When a company reduces its share count over time, each remaining share represents a larger portion of the business.

Mayer discusses AutoNation ($AN ( ▲ 0.37% )) as an excellent example of this principle. In 2000, investor Eddie Lampert (known for his work with Sears and ESL Investments) took a significant stake in the auto retailer.

Under his influence, the company implemented an aggressive buyback program, retiring 65% of its shares over the next 13 years—an average of 8.4% annually. This concentrated ownership helped drive a 520% stock price increase (15% annualized) over that period.

Warren Buffett has also established clear criteria for effective buybacks, which Mayer quotes:

“There is only one combination of facts that makes it advisable for a company to repurchase its shares: First, the company has available funds beyond the near-term needs of the business and, second, finds its stock selling in the market below its intrinsic value, conservatively calculated.”

When screening for potential 100-baggers, look for companies with a history of reducing their total shares outstanding through buybacks. The best companies repurchase shares when they're trading below their intrinsic values.

Note: Focus on companies that reduce their total shares outstanding, not just those buying back enough shares to offset stock-based compensation programs that issue new shares to executives.

Invest With Conviction

After you identify a potential 100-bagger, position sizing becomes your next key decision.

Here’s Warren Buffett’s thoughts on portfolio concentration:

"I can't be involved in 50 or 75 things. That's a Noah's Ark way of investing—you end up with a zoo that way. I like to put meaningful amounts of money in a few things."

Thomas Phelps similarly advised investors "be not tempted to shoot at anything small." The core principle is focusing your capital on stocks with 100x potential rather than diluting returns with too many holdings.

The Kelly criterion, developed by John Kelly Jr. in 1956, provides a mathematical framework for this approach:

f = edge / odds

where:

f = percentage of your portfolio you should invest

edge = your expected profit divided by your investment amount

odds = payoff you'll receive if successful

In short, this formula helps determine the optimal position size to maximize long-term growth while managing risk.

Mayer recommends a modified "half-Kelly" approach that reduces volatility while preserving most of the returns. This balanced strategy helps prevent major drawdowns while still capturing the benefits of concentration.

The main challenge in applying this to stocks is the inability to know your odds with certainty. You must make educated estimates based on your research and analysis.

Despite this challenge, many successful investors have embraced concentration.

Investors like Seth Klarman, Mohnish Pabrai, Bill Ackman, and Bruce Berkowitz maintain focused portfolios of just 4-10 positions, with their largest holdings representing significant percentages of their total investments. Their approach stands in stark contrast to typical mutual funds holding around 100 stocks, where no single position has meaningful impact.

For 100-baggers, the key takeaway is to maintain a focused portfolio of high-conviction ideas rather than a diversified collection of mediocre ones. When you finally hit that 100-bagger, you want it to significantly impact your overall returns.

Thanks for Reading!